Probiotics in Alleviating Hyperuricemia: Research Status, Mechanism of Action and Challenges

-

摘要: 高尿酸血症(Hyperuricemia,HUA)是一种由嘌呤代谢障碍所引起的,以血液中尿酸过量为特征的慢性代谢性疾病。研究表明,常规的临床治疗方法存在一定的局限性,而益生菌缓解高尿酸血症具有经济有效、毒副作用小、安全性相对较高的特点。本文主要阐述了益生菌缓解高尿酸血症的作用机制:修复肠道屏障、调节肠道微生物群;抑制黄嘌呤氧化酶的活性;加快尿酸排泄;促进嘌呤降解或代谢。益生菌在改善高尿酸血症方面具有广阔的应用前景,是未来缓解和辅助治疗高尿酸血症的重要手段。本文对高尿酸血症、益生菌缓解高尿酸血症的研究现状、作用机制及面临的挑战进行了全面地综述,以期为开发可以缓解高尿酸血症的相关益生菌制剂和营养食品及高尿酸血症的临床治疗提供理论基础和新思路。Abstract: Hyperuricemia (HUA) is a chronic metabolic disease, characterized by excessive uric acid in the blood, caused by purine metabolism disorders. Studies show that conventional clinical treatment methods have certain limitations, while probiotics have the characteristics of economical and effectiveness, with few toxic side effects, and relatively high safety for alleviating hyperuricemia. This review mainly elaborates the mechanisms of probiotics in alleviating hyperuricemia, involving repairing the intestinal barrier and regulating the gut microbiota, inhibiting the activity of xanthine oxidase, Accelerating uric acid excretion and promoting the degradation or metabolism of purine. Probiotics have broad application prospects in improving hyperuricemia, and which will be an important mean for alleviating and adjuvanting hyperuricemia in the future. This paper comprehensive reviews the research status, mechanism of action, as well as challenges of probiotics in alleviating hyperuricemia, in order to provide a theoretical basis and new ideas for the development of the related probiotic preparations and nutritional foods that can alleviate hyperuricemia, as well as clinical treatment of hyperuricemia.

-

Keywords:

- hyperuricemia /

- probiotics /

- uric acid /

- gut microbiota /

- purine

-

高尿酸血症(Hyperuricemia,HUA)是一种由嘌呤代谢障碍所引起的、以血液中尿酸过量为特征的慢性代谢性疾病。一般来说,男性尿酸水平超过420 µmol/L,女性超过350 µmol/L,即为高尿酸血症[1]。高尿酸血症初期是一种稳定的状态,85%~90%的高尿酸血症患者没有临床特征,称为无症状高尿酸血症[2]。无症状高尿酸血症引起的典型损伤包括炎症、氧化应激和肠道微生态失调,持续性的高尿酸血症可以引发痛风,即尿酸单钠晶体的沉淀导致的急性或慢性炎症和骨关节损伤[3−4]。大量的临床调查表明,高尿酸血症不仅可以发展为痛风,还经常伴有其他并发症,是高血压、高血脂、2型糖尿病、代谢综合征、慢性肾病等其他疾病的独立危险因素[5−8]。高尿酸血症正严重威胁着人类身体健康。

目前,临床上治疗高尿酸血症的方法主要有饮食控制和药物使用的方式[9]。从饮食控制的角度,可以通过限制肉类、海鲜、蘑菇等常见的富含嘌呤的食物和啤酒、果糖的摄入来进行,但这种饮食限制打破了患者的高营养价值与低嘌呤含量之间的营养均衡[10−11]。而且由于人们长期以来形成的饮食习惯,患者依从性较差,以至于限制富含嘌呤的食物的摄入难以实施[12]。临床上降低尿酸的药物包括抑制尿酸生成的药物别嘌呤醇、非布司他和促进尿酸排泄的药物苯溴马隆片等。这些药物有较好的临床效果,但同时也存在成本高、毒副作用强烈、患者耐受度低的问题,如易导致胃肠道出血、肝毒性和过敏反应等症状[13−16]。

因此,研究出经济有效且副作用小的新型药物替代物来缓解和辅助治疗高尿酸血症已刻不容缓。近些年来,较多研究表明益生菌(Probiotics)具有改善高尿酸血症的作用,高尿酸血症的临床治疗迎来了新的机遇。本文就高尿酸血症、益生菌缓解高尿酸血症的研究现状、作用机制及面临的挑战进行阐述,旨在为缓解高尿酸血症的临床应用提供参考依据,并为开发新型降尿酸益生菌食品奠定理论基础。

1. 高尿酸血症概述

1.1 尿酸形成机制

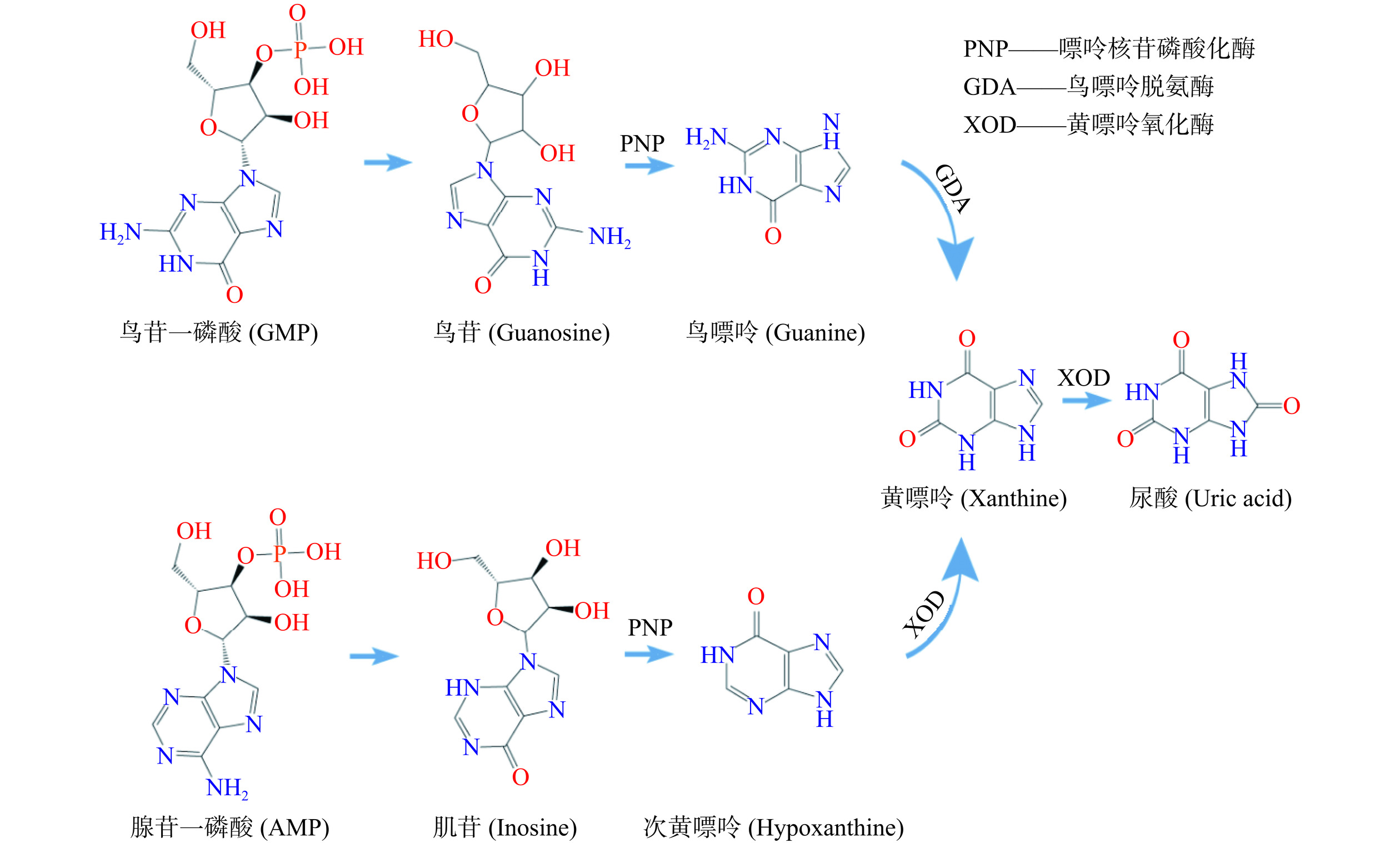

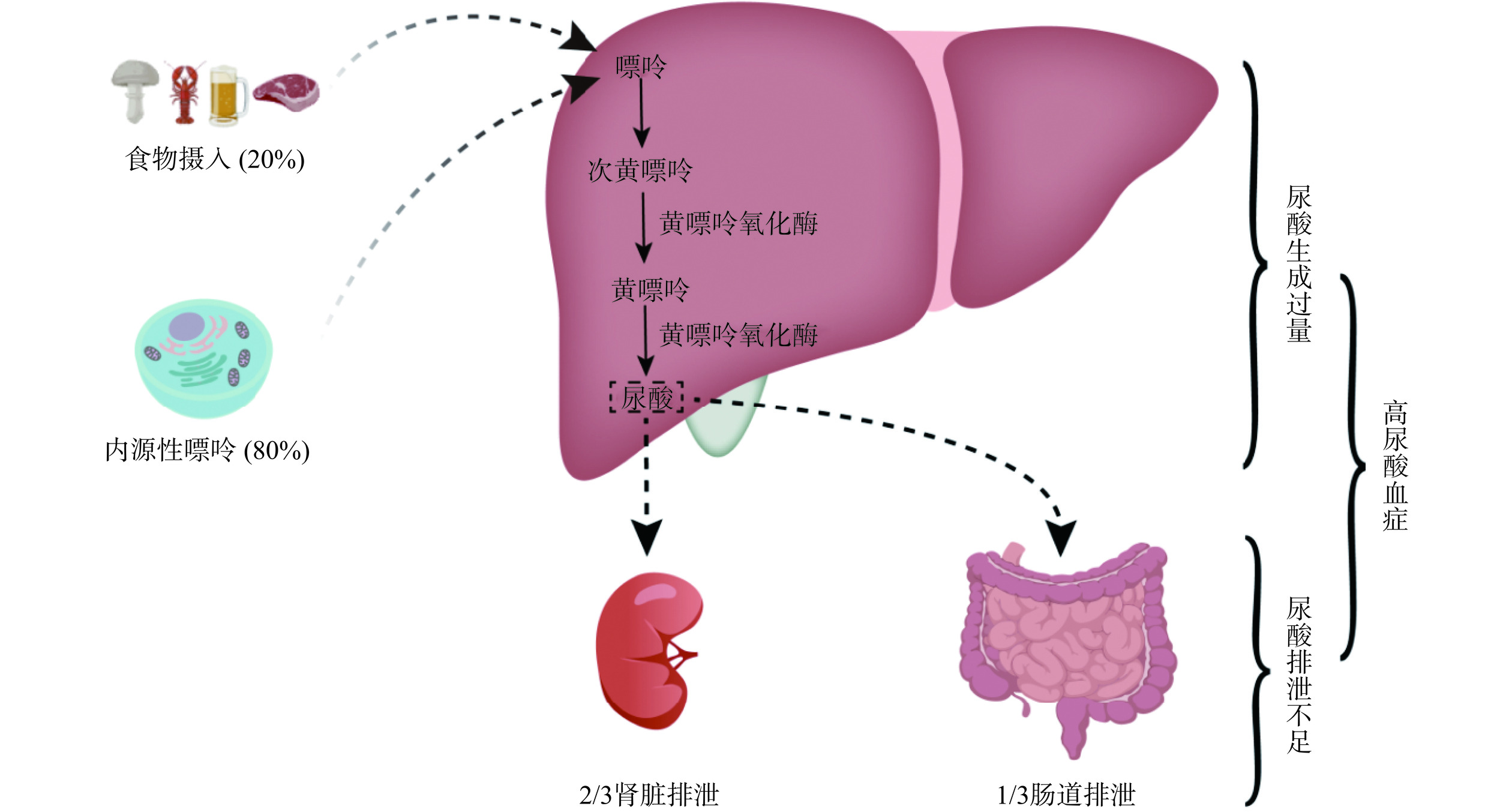

尿酸(Uric acid,UA)是人体中嘌呤代谢的最终产物,在肾小球中过滤,在肾近端小管中重吸收[17]。尿酸主要在肝脏中产生,约20%来源于富含嘌呤食物的摄入,80%由内源性嘌呤代谢产生[18−19]。尿酸的产生和代谢是一个复杂的过程。鸟苷一磷酸(Guanosine monophosphate,GMP)和腺苷一磷酸(Adenosine monophosphate,AMP)分别转化为鸟苷和肌苷,鸟苷和肌苷进一步在嘌呤核苷磷酸化酶(Purine nucleoside phosphorylase,PNP)的作用下分别转化为鸟嘌呤和次黄嘌呤,随后鸟嘌呤通过鸟嘌呤脱氨酶(Guanine deaminase,GDA)脱氨基形成黄嘌呤,次黄嘌呤被黄嘌呤氧化酶(Xanthine oxidase,XOD)氧化形成黄嘌呤,黄嘌呤再次被XOD氧化形成最终产物—尿酸[17]。图1为尿酸的形成机制。

1.2 高尿酸血症现状

血液中的尿酸水平由尿酸的形成和排泄之间的平衡来调节[20]。因此,尿酸生成过多、尿酸排泄不足或两者同时存在时,血尿酸水平就会升高,进而引起高尿酸血症甚至痛风。高尿酸血症的发病机制如图2所示。

随着我国经济的快速发展,居民的生活方式和饮食结构也发生了巨大的改变,由高嘌呤饮食引起的高尿酸血症患者数逐年增加,并呈现出年轻化的趋势[21−23]。目前,高尿酸血症已成为继糖尿病之后的第二大代谢性疾病[24],在世界范围内也是一个严重的公共卫生挑战。最新的流行病学调查结果显示,近年来,我国高尿酸血症的患病率显著上升,患病率为13.3%,高于总体水平,年增长率为9.7%,患者数量已达到1.8亿[25−26]。

研究表明,高尿酸血症是由生活方式的改变、药物使用、疾病、遗传等因素引起的。其中,不健康的生活习惯,如不规律的工作和睡眠、高脂肪和高糖饮食、酗酒、精神压力等,是促进高尿酸血症发展的最重要因素之一[27]。高尿酸血症的患病率与性别、年龄等也密切相关。男性高尿酸血症患病率明显高于女性,且随着年龄的增长而增加,绝经后女性的患病率也会升高[28−29]。Huang等[30]调查分析了中国大陆六个不同地区高尿酸血症总体患病率,发现中国男性高尿酸血症的患病率为22.7%,女性为11.0%,与先前的结论吻合。

高尿酸血症的常规治疗方法都有一定的局限性,近年来的研究表明,益生菌在降低尿酸水平、缓解高尿酸血症方面表现出无穷的潜力。

2. 益生菌缓解高尿酸血症的研究现状

2.1 具有调节高尿酸血症作用的益生菌种类

益生菌是指摄入足够数量时对宿主产生健康有益作用的活性微生物[31]。据报道,益生菌能够调节人体肠道微生物稳态、稳定胃肠道屏障功能、缓解肠胃疾病、抗氧化、抗炎、抗肿瘤、提高免疫机能,对多种疾病具有积极的调控作用,能辅助治疗过敏和肥胖症等疾病[32−34]。益生菌通过各种机制发挥其有益作用,包括降低肠道pH,减少病原微生物的定居和入侵,以及改变宿主免疫反应[35]。益生菌还是典型的膳食食品补充剂[36]。几种具有益生菌潜力的代表性乳酸菌菌株已被作为膳食补充剂食用,包括鼠李糖乳酪杆菌(Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus)、瑞士乳杆菌(Lactobactillus helveticus)、发酵粘液乳杆菌(Limosilactobacillus fermentum)、格氏乳杆菌(Lactobactillus gasseri)、德氏乳杆菌保加利亚亚种(Lactobactillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus)、嗜酸乳杆菌(Lactobactillus acidophilus)、干酪乳酪杆菌(Lacticaseibacillus casei)和罗伊氏粘液乳杆菌(Limosilactobacillus reuteri)[35]。

多年来,益生菌在医学、制药和食品领域得到了广泛的研究,常见的缓解高尿酸血症的益生菌大多来源于乳酸菌(Lactic acid bacteria,LAB),也有一些非LAB微生物,如双歧杆菌(Bifidobacteria)等[33,35,37]。LAB对人类和动物的健康有积极的作用,通常认为是安全的(Generally recognized as safe,GRAS),可作为食品和饲料中的益生菌使用[38]。LAB菌株可在肠道定植,调节高尿酸血症引起的微生态失调,促进嘌呤和尿酸代谢[39]。LAB还可以通过增加与短链脂肪酸(Short-chain fatty acids,SCFAs)生成相关的肠道菌群的丰度,促进SCFAs的产生,从而抑制血清和肝脏XOD活性,缓解高尿酸血症[40]。LAB在宿主肠道内表现出大量的抗氧化活性,促进抗氧化酶的产生,帮助宿主肠道清除活性氧,进而减少氧化损伤[41]。LAB缓解高尿酸血症的潜力逐渐引起人们的关注[42]。

2.2 益生菌缓解高尿酸血症的临床研究

研究表明,益生菌能有效降低高尿酸血症患者的尿酸水平。唾液联合乳杆菌(Ligilactobacillus salivarius)CECT 30632对肌苷、鸟苷和尿酸的转化率分别达到了100%、100%和50%。Rodríguez等[43]用其进行了一项随机临床试验研究,高尿酸血症和有痛风发作史的患者连续6个月口服L. salivarius CECT 30632后,患者血清尿酸水平显著降低,痛风发作次数减少,与氧化应激和代谢综合征有关的参数水平也有所改善。这项初步的临床试验覆盖范围小,有局限性,但揭示了L. salivarius CECT 30632在改善高尿酸血症和痛风方面极具潜力。高尿酸血症患者在服用非布司他的基础上,同时服用双歧杆菌四联活菌片,血清尿酸明显降低,与对照组(只服用非布司他)同期相比,肠道微生物丰度变化更显著,推测双歧杆菌四联活菌制剂可以通过调节肠道菌群、增强肠道细菌分解尿酸的能力,来达到降低尿酸水平的效果[44]。

L. gasseri PA-3已被证实有降尿酸作用。Kurajoh等[45]展开了一项随机、双盲、对照试验,结果表明,受试者服用添加L. gasseri PA-3的酸奶,能够降低嘌呤核苷酸诱导的血清尿酸升高的速率,适当加大服用剂量、长期服用或与有抑制XOD活性作用的食物成分联用,其降尿酸效果更好。在另一项研究中,同样地,与普通酸奶相比,含L. fermentum GR-3的益生菌酸奶显著降低了血清尿酸水平,其作用机制是调节肠道微生物群,减少宿主的炎症反应,促进尿酸排泄,保护肾脏和肠道功能[46]。

目前关于益生菌缓解高尿酸血症的研究还处于起步阶段,不够成熟,大多集中于动物试验,临床研究还相对较少,需要进行更深层次的探索,加快研究步伐,更好地应用到临床研究上。

3. 益生菌缓解高尿酸血症的作用机制

3.1 修复肠道屏障、调节肠道微生物群

肠道负责人体中1/3的尿酸排泄,尿酸分泌到肠道后,再由肠道微生物群进行代谢[47]。人体肠道中的微生物群是最大、最复杂的微生物系统,包含微生物大约有1013~1014[48]。肠道微生物群与宿主互利共生,在调节免疫系统、促进代谢、稳定肠道环境等方面发挥着重要作用,并为宿主提供能量代谢物和维生素[49]。肠道屏障由肠上皮细胞及细胞间紧密连接、粘液层、肠道微生物群和免疫防御系统组成,以防止有害物质和致病微生物转移到血液中[50]。肠道微生物群的改变和肠道屏障结构和功能的受损可导致内毒素积累,存在于革兰氏阴性菌外膜中的脂多糖(Lipopolysaccharide,LPS)可通过肠道屏障进入血液,引发全身性炎症。

高尿酸血症患者肠道屏障功能出现障碍,肠道通透性增加,微生物群多样性显著降低,肠道微生态失调,与正常人群肠道微生物群差异显著[51−52]。其中,厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)和放线菌门(Actinobacteria)相对丰度上升,拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)相对丰度下降,普氏粪杆菌(Faecalibacterium prausnitzii)和假链状双歧杆菌(Bidobacterium pseudocatenulatum)较为缺乏,而粪拟杆菌(Bacteroides caccae)和解木聚糖拟杆菌(Bacteroides xylanisolvens)富集[53−54]。 王婷婷[44]研究发现,高尿酸血症患者粪便中粪肠球菌(Enterococcus faecalis)、乳酸杆菌和双歧杆菌的含量偏低,大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)的含量偏高。以上都表明高尿酸血症患者体内肠道微生物群种类及丰度发生变化甚至紊乱,调节肠道菌群是治疗高尿酸血症的一个方向。Han等[55]通过微生物群移植试验,证实肠道微生物群在抗高尿酸血症和抗炎中具有重要作用。研究也表明粪便微生物群的失调特征与高尿酸血症或痛风有关[56]。因此,随着对肠道微生物与人体健康之间关系的深入认识,肠道菌群被确定为治疗高尿酸血症的新靶点[27]。

益生菌可以通过修复肠道屏障、调节肠道菌群降低尿酸水平。研究发现,L. fermentum 2644通过上调高尿酸血症大鼠结肠的紧密连接蛋白occludin和粘蛋白2(Mucin 2)的基因表达,增强了肠道屏障功能,L. rhamnosus 1155可以改善高尿酸血症诱导的肠道微生物群失调[57]。短乳杆菌(Levilactobacillus brevis)DM9218可以通过降解肌苷来延缓尿酸的积累,调节肠道生态失调,使肠道屏障功能增强,肝脏LPS减少,降低果糖诱导的高尿酸血症小鼠的尿酸水平[58]。益生菌L. fermentum F40-4和L. fermentum GR-3通过调节小鼠肠道微生物群和减轻炎症来降低尿酸水平,改善高尿酸血症[59]。

植物乳植杆菌(Lactiplantibacillus plantarum)TCI227促进了SCFAs的产生增加了乳杆菌属(Lactobacillus)、乳杆菌科(Lactobacillaceae)和瘤胃球菌属(Ruminococcus)的水平,降低了普雷沃氏菌属(Prevotella)、普雷沃氏菌科(Prevotellaceae)和脱铁杆菌科(Deferribacteraceae)的水平,表明L. plantarum TCI227可以调节肠道菌群的组成来改善氧嗪酸钾(Potassium oxazinate,PO)诱导的高尿酸血症大鼠的尿酸水平[60]。副干酪乳酪杆菌(Lacticaseibacillus paracasei)MJM60396能使紧密连接蛋白ZO-1和occludin表达增加,与肠屏障完整性相关的Muribaculaceae和毛螺菌科(Lachnospiraceae)细菌的相对丰度增加,恢复受损的肠道屏障[61]。戊糖乳植杆菌(Lactiplantibacillus pentosus)P2020通过降低厚壁菌门与拟杆菌门的比值(F/B),抑制NF-κB、TNF、MAPK信号通路,降低了炎症水平,保护肠道屏障,恢复了肠道微生物群的组成,减少了肾脏损伤[62]。

由此可见,益生菌通过修复肠道屏障,改善肠道通透性,减轻炎症,调节肠道微生物群的比例和丰度,最终达到降低尿酸的效果。肠道菌群作为未来调节高尿酸血症的靶点,其与益生菌的相互作用关系需进一步阐明。

3.2 抑制XOD的活性

XOD是一种用途广泛的酶,广泛分布于各物种中,参与嘌呤代谢、尿酸生成,是尿酸合成中的关键酶[63−64]。在人体中,XOD催化次黄嘌呤氧化为黄嘌呤,再氧化黄嘌呤最终形成尿酸。然而人类在进化过程中丢失了将尿酸氧化为水溶性的尿囊素的关键酶—尿酸氧化酶(Urate oxidase,UOX),与低等动物相比,血液中尿酸水平相对较高,更易引发高尿酸血症[65]。因此,抑制XOD的氧化活性可以有效降低血尿酸水平。

牛春华等[66]发现L. plantarum UA149可以显著降低PO和果糖诱导的高尿酸血症大鼠的XOD含量和血尿酸含量,达到治疗高尿酸血症的目的。L. brevis DM9218可以下调肝脏XOD的表达和活性,防止高果糖诱导的肝损伤[58]。L. plantarum Q7对尿酸代谢的影响能力较强,可以使XOD的活性下调29.41%[67]。L. paracasei X11可使XOD的水平降低44.60%[68]。L. rhamnosus 1155显著抑制了肝脏和血清中XOD的活性,有利于减少尿酸生成[57]。在动物体内研究中,口服2周L. brevis MJM60390后,XOD的活性被抑制了30%,血清中尿酸水平显著降低至正常水平[69]。口服3周L. paracasei MJM60396后,小鼠的XOD活性被降低了81%[61]。Cao等[59]研究发现,L. fermentum F40-4可使尿酸和XOD水平分别降低40.84%、41.79%,表明L. fermentum F40-4可作为潜在的益生菌预防和治疗高尿酸血症。

尿酸生成需要XOD的催化,益生菌可能通过抑制XOD的表达和活性水平,减少尿酸在体内的生成,从源头上控制了尿酸水平的升高,这表明对XOD的抑制是以后缓解高尿酸血症的研究重点,有待更进一步探索。

3.3 加快尿酸排泄

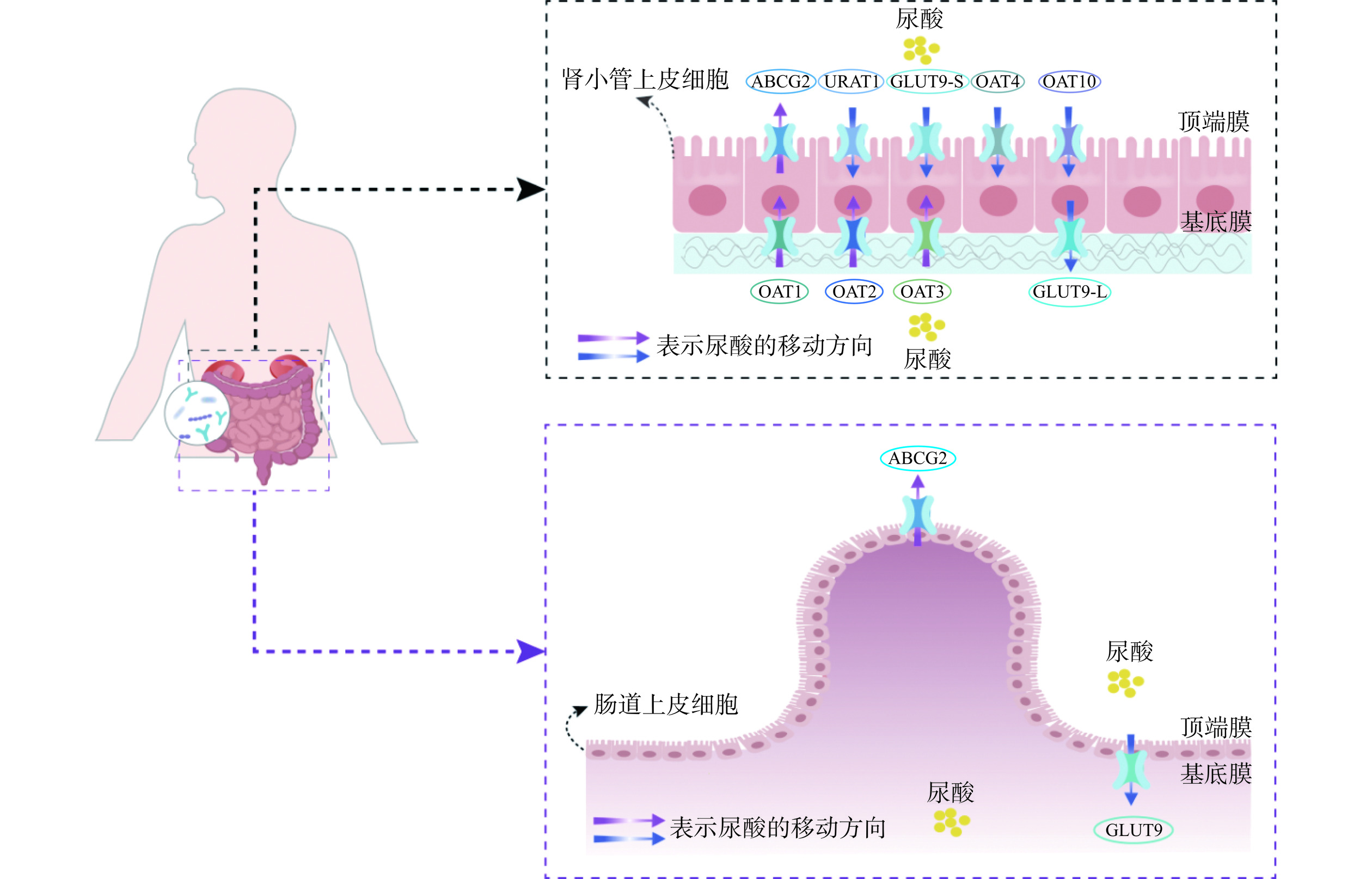

尿酸在肝脏中形成后,约2/3经过肾脏排出,1/3由肠道排出,即肾外排泄途径[7]。人体内的尿酸在肝脏、肾脏和肠道的作用下保持着一种动态的平衡[17]。临床上,原发性高尿酸血症的致病原因包括肝脏和肾脏中尿酸过度生成或肾外尿酸分泌不足,尿酸排泄不良占比高达90%,具体取决于在基底膜和顶端膜表达的尿酸转运蛋白[70−72]。在肾小球过滤后,尿酸通过各种尿酸转运蛋白在肾近端小管中重吸收和分泌:一种是尿酸分泌转运蛋白,能将尿酸从血液运输到尿液或粪便,包括有机阴离子转运蛋白OAT1、OAT3和ATP 结合盒亚家族G成员2(ABCG2)等;另一种是尿酸重吸收转运蛋白,能将尿酸重吸收到血液循环中,如有机阴离子转运蛋白OAT4、OAT10、尿酸重吸收转运蛋白1(Urate anion transporter 1,URAT1)、葡萄糖转运蛋白9(Glucose transporter 9,GLUT9)等[73−74]。这些尿酸转运体的表达过量或不足会改变体内尿酸的平衡,导致患高尿酸血症的风险增加[75]。ABCG2介导了肾脏和肾外(肠道)尿酸排泄,在肾、肝、肠等多种组织的顶端膜上表达,是肠道中的主要转运蛋白,在肠道尿酸排泄和高尿酸血症的发病机制中起着重要作用,其功能障碍降低了肠道内尿酸的排泄,导致血尿酸水平升高,约占痛风患者的80%[76−78]。尿酸转运蛋白在肾脏和肠道中的分布如图3所示。

益生菌能够上调尿酸分泌转运蛋白的基因表达,下调尿酸重吸收转运蛋白的基因表达,进而调节尿酸水平。L. plantarum Q7通过降低尿酸重吸收转运蛋白、促进尿酸分泌转运蛋白基因表达来调节尿酸水平,GLUT9和URAT1的表达分别降低了31.22%和30.89%[67]。L. rhamnosus 1155和L. fermentum 2644上调了结肠和空肠组织中ABCG2的基因表达,显著提高了粪便尿酸水平,加快了肠道内尿酸排泄[57]。L. rhamnosus Fmb14上调ABCG2在mRNA水平上的表达,抑制了GLUT9的生物合成,来改善高尿酸血症,肌苷诱导的高尿酸血症模型小鼠口服8周L. rhamnosus Fmb14 后,其尿酸水平从236.28 µmol/L降至149.28 µmol/L,表明L. rhamnosus Fmb14在预防高尿酸血症方面具有潜力[79]。L. paracasei MJM60396增加了小鼠OAT1和OAT3的表达,降低了URAT1和GLUT9的表达,抑制尿酸的重吸收、促进尿酸排泄来调节血清尿酸水平[61]。

尿酸的排泄依赖于体内的尿酸转运蛋白。益生菌促进了尿酸分泌转运蛋白的表达,同时抑制了尿酸重吸收转运蛋白的表达,加快尿酸排泄,进而降低尿酸水平,其具体作用机制需要更深入的研究。

3.4 促进嘌呤降解或代谢

嘌呤在体内主要以嘌呤核苷酸的形式存在,在XOD的一系列催化作用下转变为尿酸。嘌呤代谢受损时,血清尿酸水平会升高形成高尿酸血症,最终导致痛风。因此,促进嘌呤降解也是降低尿酸水平的有效途径,开发高效降解嘌呤类化合物的益生菌是预防高尿酸血症的一种有前景的替代疗法。

Lu等[80]从中国发酵米粉中分离出一株新的降解嘌呤的乳酸菌菌株,命名为L. fermentum 9-4,并研究其在嘌呤降解食品开发中的潜在应用,发现L. fermentum 9-4能有效降解肌苷和鸟苷,对鸟苷的同化率高达(55.93±3.12)%,表明L. fermentum 9-4可能在开发低嘌呤食品中具有潜在的应用前景。L. casei ZM15有较强的降解核苷酸(腺苷酸、鸟苷酸)和核苷(腺苷、鸟苷)能力,且降解率可达100%,推测其作用机制是通过在肠道内与肠道上皮细胞竞争吸收核苷与核苷酸来降低尿酸[81]。L. brevis DM9218通过降解嘌呤代谢中间体、L. gasseri PA-3减少了肠道对食物中嘌呤的吸收来治疗高尿酸血症[58,82]。L. reuteri TSR332和L. fermentum TSF331菌株,可以通过利用嘌呤减少尿酸合成[83]。L. rhamnosus 1155和L. fermentum 2644具有较强鸟苷转化和降解能力,L. fermentum 2644对鸟苷的转化率和降解率分别为100.00%、55.10%。体内试验结果表明,给予L. fermentum 2644或L. fermentum 1155可使大鼠的尿酸水平下降20%以上,粪便尿酸水平升高[84]。L. acidophilus F02对肌苷的降解率为94.26%,降低了肠道对核苷的吸收[85]。Li等[86]发现L. plantarum中的三种核糖核苷水解酶RihA、B、C可以催化核苷降解为碱基、次黄嘌呤和黄嘌呤,且L. plantarum中不存在催化次黄嘌呤和黄嘌呤转化为黄嘌呤和尿酸的酶,一定程度上阻断了尿酸合成途径,从而降低了尿酸水平。益生菌通过与肠道上皮细胞竞争吸收核苷,用于自身生长繁殖的需要,或降解嘌呤,导致尿酸生成减少,从而降低尿酸水平。

综上所述,益生菌可以减少尿酸生成和促进尿酸排泄,缓解高尿酸血症,实现途径主要包括:促进肠道紧密连接蛋白和粘蛋白的表达,修复肠道屏障,改善其通透性,减轻炎症,调节肠道微生物群的种类和丰度;抑制XOD的活性,减少尿酸在体内的生成;调节ABCG2、URAT1和GLUT9等尿酸转运蛋白的基因表达,加快尿酸排出体外,降低尿酸;降解核苷与核苷酸、与肠道上皮细胞竞争吸收核苷,减少肠道对嘌呤物质的吸收。表1为益生菌缓解高尿酸血症的作用机制相关研究。

表 1 益生菌缓解高尿酸血症的作用机制相关研究Table 1. Studies on the mechanism of action of probiotics in alleviating hyperuricemia作用机制 益生菌 作用效果 参考文献 修复肠道屏障,调节肠道微生物群 L. fermentum JL-3 调节高尿酸血症小鼠肠道微生物群的结构和功能,减轻肝脏氧化应激和

炎症指标,减少肾脏损伤[39] L. pentosus ZS4502 恢复肠道菌群平衡,拟杆菌科和毛螺菌科丰度相对降低,

乳杆菌科和双歧杆菌科丰度相对升高[87] L. pentosus P2020 降低厚壁菌门与拟杆菌门的比值,抑制NF-κB、TNF、MAPK信号通路,

降低炎症水平,保护肠道屏障,恢复肠道微生物群的组成[62] L. gasseri LG08、Leuconostoc

mesenteroides LM58调节肠道微生物群结构,降低厚壁菌门与拟杆菌门的比值,显著增加Alistipes,

减轻炎症,提高机体抗氧化能力[88] wild-type E. coli

Nissle 1917调节肠道菌群,恢复到正常水平 [89] 抑制XOD的活性 L. Rhamnosus R31、

L. rhamnosus R28-1、

L. reuteri L20M3有效降低肝脏中XOD活性水平 [40] L. Rhamnosus 1155 显著抑制肝脏和血清中XOD的活性,减少尿酸的产生 [57] L. plantarum Q7 使XOD的活性降低29.41% [67] L. plantarum UA149 血清XOD活性降低15.36% [66] L. fermentum F40-4 XOD水平降低41.79% [59] L. plantarum LLY-606 显著抑制了肝脏中XOD的表达水平 [90] 加快尿酸排泄 L. brevis PDD-5 下调URAT1和GLUT9基因表达,上调OAT1基因表达 [91] E. faecalis W5 上调ABCG2的表达,下调GLUT9的表达 [92] L. rhamnosus 1155、

L. fermentum 2644上调ABCG2的基因表达,加快尿酸排泄 [57] L. paracasei X11 分别降低GLUT9和URAT1的表达24.39%和24.69% [68] L. rhamnosus Fmb14 上调ABCG2的表达,抑制GLUT9 [79] Akkermansia muciniphila 肾脏中URAT1和GLUT9显著下调,肠道中ABCG2的mRNA和蛋白表达增加 [93] 促进嘌呤降解或代谢 L. gasseri PA-3 吸收GMP、鸟苷、IMP、肌苷和次黄嘌呤 [82] L. reuteri TSR332、

L. fermentumTSF331吸收肌苷(90%)和鸟苷(78%),尿酸降低60% [83] L. casei ZM15 对核苷酸和核苷的降解率达100% [81] L. acidophilus F02 对肌苷的降解率为94.26% [85] L. plantarum X7022 鸟嘌呤、黄嘌呤和腺嘌呤分别降低了33.1%、82.2%和12.6% [94] L. plantarum X7023 鸟嘌呤、黄嘌呤和腺嘌呤分别降低了21.4%、93.9%和11.5% [95] 4. 益生菌缓解高尿酸血症面临的挑战

益生菌为治疗高尿酸血症提供了新思路,相较于饮食控制和药物治疗,益生菌拥有诸多优势,也被认为是未来治疗高尿酸血症的重要途径,但同时也存在一些问题。

4.1 益生菌的安全性

作为一种潜在的治疗干预手段,益生菌已引起研究者广泛关注,但其安全性尚未得到系统评价的充分证据支持[96]。安全使用史是对目前许多益生菌安全性评估的支柱。因此,必须慎重考虑那些来源于没有安全使用史的物质的益生菌的安全性。然而,全球尚未协调统一在食品和补充剂中使用的益生菌的安全要求[38]。此外,即使食用相同的益生菌产品,其功效和副作用也因个体而异[97]。例如,在健康人群和部分免疫功能正常的患病人群中,益生菌表现出的急性安全问题并不明显;但在一些高危人群,如免疫功能低下的群体中,虽然有报道称益生菌对这类群体有益,但他们也可能因抵御微生物的能力减弱而导致发生不良反应的风险更高,益生菌甚至可能表现为条件致病菌,即免疫功能正常的人服用益生菌是安全有效的,但在免疫抑制条件下存在不确定性[98−101]。

4.2 益生菌的肠道定植与存活

益生菌筛选的主要标准是其能够在人体肠道内定植与存活,即能够黏附在宿主肠道上皮细胞表面,并能在胃肠道环境中存活[102]。目前,大量证据表明,大多数益生菌未在肠道内定植[103]。抵抗胃肠环境、胃酸耐受性和胆盐耐受性也是适于口服途径使用的益生菌存活的关键重要特性[104]。菌株需抵御不良的胃肠环境,并存活一定的数量后才能够发挥益生作用[105]。而胃和肠道具有高酸性pH值和高胆盐浓度[106],对益生菌的活性影响较大,综合定植和胃肠道条件来看,满足条件的益生菌种类较少。Li等[107]从中国泡菜中分离出三株对肌苷和鸟苷有较强降解能力的乳酸菌,DM9218、DM9242和DM9505,三种菌株对酸的耐受程度中等,对胆盐的耐受性较差。胆盐浓度为0.3%时,没有菌株生长,DM9505甚至无法在含0.1%胆盐的培养基中生长。DM9242和DM9218对细胞粘附能力强,而DM9505相对较弱。对DM9218进行培养驯化后,其耐胆盐能力有所提升,得以在大鼠肠道中定植存活,可以作为缓解高尿酸血症的候选益生菌。因此,对分离出的菌株定向培养也许有助于其定植存活。研究表明,对益生菌封装如微胶囊化可以提高益生菌在胃肠道中的存活率,保留益生菌的特性和活力[108]。

4.3 益生菌的体内和临床研究相对缺乏

目前益生菌调节尿酸的体外模拟试验效果较好。然而,体内和临床应用研究较少,益生菌能否在人体内发挥作用还需要在临床上进一步验证。益生菌缓解高尿酸血症的研究尚且处于初级阶段,作用机制可能还不够完善,也不确定益生菌是否还存在其他的降尿酸机制,还需要深入探索益生菌缓解高尿酸血症的途径,扩大临床研究规模。

5. 结论与展望

高尿酸血症正严重影响着人类的健康和生活质量。益生菌可多途径缓解高尿酸血症,其作用机制主要包括修复肠道屏障、调节肠道微生物群、抑制 XOD的活性、加快尿酸排泄以及促进嘌呤降解或代谢。益生菌干预调节高尿酸血症经济、有效且副作用较小,这使得益生菌在改善高尿酸血症方面具有广阔的发展前景和应用前景。

然而,目前益生菌缓解高尿酸血症的研究还处于初级阶段,尚且不确定益生菌是否还存在其他的降尿酸机制,深入探索其作用机制是未来的研究方向之一。修复肠道屏障和调节肠道微生物群不仅与降低尿酸水平有关,也和其他疾病的治疗密切相关,应是未来研究的重中之重,粪菌移植可能是一个突破口。高尿酸血症多由尿酸排泄不足引起,因此,与尿酸排泄有关的尿酸转运蛋白也是一个攻克方向。目前已知的具有缓解高尿酸血症作用的益生菌菌株较少,需加强对新型降尿酸菌株的分离筛选,特别是人体内缺乏UOX,可以将筛选出产尿酸氧化酶的菌株作为研究方向之一,扩大菌株资源库。此外,试验动物和人体之间存在一定的生理和代谢等的差异,试验动物的效果无法完全反映人体的效果,过去的研究大多数是围绕动物展开,未来的研究重点应该聚焦于体内试验和临床试验,需进一步提高益生菌缓解高尿酸血症的研究水平,加大研究力度,将其应用到临床实践中。加强对益生菌的降尿酸效果和系统安全性评估,确保益生菌缓解高尿酸血症的有效性和安全性。本文可为益生菌调节高尿酸血症的后续研究和为开发新型降尿酸益生菌制剂与功能性食品奠定理论基础和提供新思路。

-

表 1 益生菌缓解高尿酸血症的作用机制相关研究

Table 1 Studies on the mechanism of action of probiotics in alleviating hyperuricemia

作用机制 益生菌 作用效果 参考文献 修复肠道屏障,调节肠道微生物群 L. fermentum JL-3 调节高尿酸血症小鼠肠道微生物群的结构和功能,减轻肝脏氧化应激和

炎症指标,减少肾脏损伤[39] L. pentosus ZS4502 恢复肠道菌群平衡,拟杆菌科和毛螺菌科丰度相对降低,

乳杆菌科和双歧杆菌科丰度相对升高[87] L. pentosus P2020 降低厚壁菌门与拟杆菌门的比值,抑制NF-κB、TNF、MAPK信号通路,

降低炎症水平,保护肠道屏障,恢复肠道微生物群的组成[62] L. gasseri LG08、Leuconostoc

mesenteroides LM58调节肠道微生物群结构,降低厚壁菌门与拟杆菌门的比值,显著增加Alistipes,

减轻炎症,提高机体抗氧化能力[88] wild-type E. coli

Nissle 1917调节肠道菌群,恢复到正常水平 [89] 抑制XOD的活性 L. Rhamnosus R31、

L. rhamnosus R28-1、

L. reuteri L20M3有效降低肝脏中XOD活性水平 [40] L. Rhamnosus 1155 显著抑制肝脏和血清中XOD的活性,减少尿酸的产生 [57] L. plantarum Q7 使XOD的活性降低29.41% [67] L. plantarum UA149 血清XOD活性降低15.36% [66] L. fermentum F40-4 XOD水平降低41.79% [59] L. plantarum LLY-606 显著抑制了肝脏中XOD的表达水平 [90] 加快尿酸排泄 L. brevis PDD-5 下调URAT1和GLUT9基因表达,上调OAT1基因表达 [91] E. faecalis W5 上调ABCG2的表达,下调GLUT9的表达 [92] L. rhamnosus 1155、

L. fermentum 2644上调ABCG2的基因表达,加快尿酸排泄 [57] L. paracasei X11 分别降低GLUT9和URAT1的表达24.39%和24.69% [68] L. rhamnosus Fmb14 上调ABCG2的表达,抑制GLUT9 [79] Akkermansia muciniphila 肾脏中URAT1和GLUT9显著下调,肠道中ABCG2的mRNA和蛋白表达增加 [93] 促进嘌呤降解或代谢 L. gasseri PA-3 吸收GMP、鸟苷、IMP、肌苷和次黄嘌呤 [82] L. reuteri TSR332、

L. fermentumTSF331吸收肌苷(90%)和鸟苷(78%),尿酸降低60% [83] L. casei ZM15 对核苷酸和核苷的降解率达100% [81] L. acidophilus F02 对肌苷的降解率为94.26% [85] L. plantarum X7022 鸟嘌呤、黄嘌呤和腺嘌呤分别降低了33.1%、82.2%和12.6% [94] L. plantarum X7023 鸟嘌呤、黄嘌呤和腺嘌呤分别降低了21.4%、93.9%和11.5% [95] -

[1] WU X H, YOU C G. The biomarkers discovery of hyperuricemia and gout:Proteomics and metabolomics[J]. Peer J,2023,11:e14554.

[2] SUN H L, WU Y W, BIAN H G, et al. Function of uric acid transporters and their inhibitors in hyperuricaemia[J]. Frontiers in Pharmacology,2021,12:667753. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.667753

[3] ZHAO H Y, LU Z X, LU Y J. The potential of probiotics in the amelioration of hyperuricemia[J]. Food & Function,2022,13(5):2394−2414.

[4] LIU W J, PENG J, WU Y X, et al. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms and therapeutic targets of gout:An update[J]. International Immunopharmacology,2023,121:110466. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110466

[5] MALLA P, KHANAL M P, POKHREL A, et al. Correlation of serum uric acid and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council,2023,21(1):170−174.

[6] CHEN Y Y, KAO T W, YANG H F, et al. The association of uric acid with the risk of metabolic syndrome, arterial hypertension or diabetes in young subjects-an observational study[J]. Clinica Chimica Acta,2018,478:68−73. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2017.12.038

[7] KIELSTEIN J T, PONTREMOLI R, BURNIER M. Management of hyperuricemia in patients with chronic kidney disease:a focus on renal protection[J]. Current Hypertension Reports,2020,22(12):102. doi: 10.1007/s11906-020-01116-3

[8] GAMALA M, JACOBS J W. Gout and hyperuricaemia:a worldwide health issue of joints and beyond[Z]. Oxford University Press, 2019, (58)12:2083−2085.

[9] POON S H, HALL H A, ZIMMERMANN B. Approach to the treatment of hyperuricemia[J]. Rhode Island Medical Journal,2009,92(11):359−362.

[10] ZHANG R, GAO S J, ZHU C Y, et al. Characterization of a novel alkaline Arxula adeninivorans urate oxidase expressed in Escherichia coli and its application in reducing uric acid content of food[J]. Food Chemistry,2019,293:254−262. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.04.112

[11] VILLEGAS R, XIANG Y B, ELASY T, et al. Purine-rich foods, protein intake, and the prevalence of hyperuricemia:the Shanghai Men’s Health Study[J]. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases,2012,22(5):409−416. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.07.012

[12] KANEKO K, AOYAGI Y, FUKUUCHI T, et al. Total purine and purine base content of common foodstuffs for facilitating nutritional therapy for gout and hyperuricemia[J]. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin,2014,37(5):709−721. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b13-00967

[13] TAUSCHE A K, JANSEN T L, SCHRÖDER H E, et al. Gout—current diagnosis and treatment[J]. Deutsches Ä rzteblatt International,2009,106(34-35):549−555.

[14] CAO Z H, WEI Z Y, ZHU Q Y, et al. HLA-B* 58:01 allele is associated with augmented risk for both mild and severe cutaneous adverse reactions induced by allopurinol in Han Chinese[J]. Pharmacogenomics,2012,13(10):1193−1201. doi: 10.2217/pgs.12.89

[15] ISHIKAWA T, MAEDA T, HASHIMOTO T, et al. Long-term safety and effectiveness of the xanthine oxidoreductase inhibitor, topiroxostat in Japanese hyperuricemic patients with or without gout:A 54-week open-label, multicenter, post-marketing observational study[J]. Clinical Drug Investigation,2020,40(9):847−859. doi: 10.1007/s40261-020-00941-3

[16] AZEEZ S, N M K, P V. Medicinal plants for hyperuricemia and gout:A review[J]. Journal of Contemporary Medical Practice,2022,4(12):90−95.

[17] MAIUOLO J, OPPEDISANO F, GRATTERI S, et al. Regulation of uric acid metabolism and excretion[J]. International Journal of Cardiology,2016,213:8−14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.08.109

[18] 孙琳, 王桂侠, 郭蔚莹. 高尿酸血症研究进展[J]. 中国老年学杂志,2017,37(4):1034−1038. [SUN L, WANG G X, GUO W Y. Research progress in hyperuricemia[J]. Chinese Journal of Gerontology,2017,37(4):1034−1038.] doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-9202.2017.04.112 SUN L, WANG G X, GUO W Y. Research progress in hyperuricemia[J]. Chinese Journal of Gerontology, 2017, 37(4): 1034−1038. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-9202.2017.04.112

[19] PAN L B, HAN P, MA S R, et al. Abnormal metabolism of gut microbiota reveals the possible molecular mechanism of nephropathy induced by hyperuricemia[J]. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B,2020,10(2):249−261. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.10.007

[20] DE OLIVEIRA E P, BURINI R C. High plasma uric acid concentration:Causes and consequences[J]. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome,2012,4(1):1−7.

[21] SHAN R Q, NING Y, MA Y, et al. Incidence and risk factors of hyperuricemia among 2.5 million Chinese adults during the years 2017–2018[J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,2021,18(5):2360. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052360

[22] YOKOSE C, MCCORMICK N, CHOI H K. The role of diet in hyperuricemia and gout[J]. Current Opinion in Rheumatology,2021,33(2):135−144. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000779

[23] SUN Y Y, SUN J P, ZHANG P P, et al. Association of dietary fiber intake with hyperuricemia in US adults[J]. Food & Function,2019,10(8):4932−4940.

[24] ZHAO R, LI Z M, SUN Y Q, et al. Engineered Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 with urate oxidase and an oxygen-recycling system for hyperuricemia treatment[J]. Gut Microbes,2022,14(1):2070391. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2022.2070391

[25] SONG D N, ZHAO H H, WANG L L, et al. Ethanol extract of Sophora japonica flower bud, an effective potential dietary supplement for the treatment of hyperuricemia[J]. Food Bioscience,2023,52:102457. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2023.102457

[26] ZHANG M, ZHU X X, WU J, et al. Prevalence of hyperuricemia among Chinese adults:findings from two nationally representative cross-sectional surveys in 2015–16 and 2018–19[J]. Frontiers in Immunology,2022,12:791983. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.791983

[27] LI L Z, WANG X M, FENG X J, et al. Effects of a macroporous resin extract of Dendrobium officinale leaves in rats with hyperuricemia induced by anthropomorphic unhealthy lifestyle[J]. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine,2023,2023:9990843. doi: 10.1155/2023/9990843

[28] ANTELO-PAIS P, PRIETO-DÍAZ M Á, MICÓ-PÉREZ R M, et al. Prevalence of hyperuricemia and its association with cardiovascular risk factors and subclinical target organ damage[J]. Journal of Clinical Medicine,2022,12(1):50. doi: 10.3390/jcm12010050

[29] DEHLIN M, JACOBSSON L, RODDY E. Global epidemiology of gout:prevalence, incidence, treatment patterns and risk factors[J]. Nature Reviews Rheumatology,2020,16(7):380−390. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-0441-1

[30] HUANG J Y, MA Z F, ZHANG Y T, et al. Geographical distribution of hyperuricemia in mainland China:A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Global Health Research and Policy,2020,5(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s41256-020-00178-9

[31] HILL C, GUARNER F, REID G, et al. Expert consensus document:The international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic[J]. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology,2014,11(8):506−514 .

[32] ELISASHVILI V, KACHLISHVILI E, CHIKINDAS M L. Recent advances in the physiology of spore formation for Bacillus probiotic production[J]. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins,2019,11(3):731−747. doi: 10.1007/s12602-018-9492-x

[33] VERA-SANTANDER V E, HERNÁNDEZ-FIGUEROA R H, JIMÉNEZ-MUNGUÍA M T, et al. Health benefits of consuming foods with bacterial probiotics, postbiotics, and their metabolites:A review[J]. Molecules,2023,28(3):1230−1257. doi: 10.3390/molecules28031230

[34] ZUCKO J, STARCEVIC A, DIMINIC J, et al. Probiotic-friend or foe?[J]. Current Opinion in Food Science,2020,32:45−49. doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2020.01.007

[35] WILLIAMS N T. Probiotics[J]. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy,2010,67(6):449−458. doi: 10.2146/ajhp090168

[36] SHI L H, BALAKRISHNAN K, THIAGARAJAH K, et al. Beneficial properties of probiotics[J]. Tropical Life Sciences Research,2016,27(2):73−90. doi: 10.21315/tlsr2016.27.2.6

[37] HOLZAPFEL W H, WOOD B J. Lactic acid bacteria:biodiversity and taxonomy[M]. New York:John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

[38] ROE A L, BOYTE M E, ELKINS C A, et al. Considerations for determining safety of probiotics:A USP perspective[J]. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology,2022,136:105266. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2022.105266

[39] WU Y, YE Z, FENG P Y, et al. Limosilactobacillus fermentum JL-3 isolated from ''Jiangshui'' ameliorates hyperuricemia by degrading uric acid[J]. Gut Microbes,2021,13(1):1897211. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1897211

[40] NI C X, LI X, WANG L L, et al. Lactic acid bacteria strains relieve hyperuricaemia by suppressing xanthine oxidase activity via a short-chain fatty acid-dependent mechanism[J]. Food & Function,2021,12(15):7054−7067.

[41] FENG T, WANG J. Oxidative stress tolerance and antioxidant capacity of lactic acid bacteria as probiotic:A systematic review[J]. Gut Microbes,2020,12(1):1801944. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2020.1801944

[42] LIN J X, XIONG T, PENG Z, et al. Novel lactic acid bacteria with anti-hyperuricemia ability:screening and in vitro probiotic characteristics[J]. Food Bioscience,2022,49:101840. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2022.101840

[43] RODRÍGUEZ J M, GARRANZO M, SEGURA J, et al. A randomized pilot trial assessing the reduction of gout episodes in hyperuricemic patients by oral administration of Ligilactobacillus salivarius CECT 30632, a strain with the ability to degrade purines[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology,2023,14:1111652. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1111652

[44] 王婷婷. 双歧杆菌四联活菌辅助治疗对高尿酸血症的临床效果分析[J]. 医学食疗与健康,2021,19(3):95−96,98. [WANG T T. Clinical effect analysis of adjuvant therapy of bifidobacterium quadruple bacteria in hyperuricemia[J]. Medical Diet and Health,2021,19(3):95−96,98.] WANG T T. Clinical effect analysis of adjuvant therapy of bifidobacterium quadruple bacteria in hyperuricemia[J]. Medical Diet and Health, 2021, 19(3): 95−96,98.

[45] KURAJOH M, MORIWAKI Y, KOYAMA H, et al. Yogurt containing Lactobacillus gasseri PA-3 alleviates increases in serum uric acid concentration induced by purine ingestion:A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study[J]. Gout and Nucleic Acid Metabolism,2018,42(1):31−40. doi: 10.6032/gnam.42.31

[46] ZHAO S, FENG P Y, HU X G, et al. Probiotic Limosilactobacillus fermentum GR-3 ameliorates human hyperuricemia via degrading and promoting excretion of uric acid[J]. Iscience,2022,25(10):105198. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.105198

[47] WANG J, CHEN Y, ZHONG H, et al. The gut microbiota as a target to control hyperuricemia pathogenesis:potential mechanisms and therapeutic strategies[J]. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition,2022,62(14):3979−3989. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2021.1874287

[48] HU Y H, XIE Y, SU Q T, et al. Probiotic and safety evaluation of twelve lactic acid bacteria as future probiotics[J]. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease,2023,20(11):521−530. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2023.0039

[49] MAFRA D, LOBO J C, BARROS A F, et al. Role of altered intestinal microbiota in systemic inflammation and cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease[J]. Future Microbiology,2014,9(3):399−410. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.165

[50] REN Z H, GUO C Y, YU S M, et al. Progress in mycotoxins affecting intestinal mucosal barrier function[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences,2019,20(11):2777. doi: 10.3390/ijms20112777

[51] XU D X, LÜ Q L, WANG X F, et al. Hyperuricemia is associated with impaired intestinal permeability in mice[J]. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology,2019,317(4):G484−G492. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00151.2019

[52] SHENG S F, CHEN J F, ZHANG Y H, et al. Structural and functional alterations of gut microbiota in males with hyperuricemia and high levels of liver enzymes[J]. Frontiers in Medicine,2021,8:779994. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.779994

[53] LIU X, LÜ Q L, REN H Y, et al. The altered gut microbiota of high-purine-induced hyperuricemia rats and its correlation with hyperuricemia[J]. Peer J,2020,8:e8664. doi: 10.7717/peerj.8664

[54] GUO Z, ZHANG J C, WANG Z L, et al. Intestinal microbiota distinguish gout patients from healthy humans[J]. Scientific Reports,2016,6(1):20602. doi: 10.1038/srep20602

[55] HAN J J, WANG Z Y, LU C Y, et al. The gut microbiota mediates the protective effects of anserine supplementation on hyperuricaemia and associated renal inflammation[J]. Food & Function,2021,12(19):9030−9042.

[56] HE S H, XIONG Q Q, TIAN C, et al. Inulin-type prebiotics reduce serum uric acid levels via gut microbiota modulation:A randomized, controlled crossover trial in peritoneal dialysis patients[J]. European Journal of Nutrition,2022(61):665−677.

[57] LI Y J, ZHU J, LIN G D, et al. Probiotic effects of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus 1155 and Limosilactobacillus fermentum 2644 on hyperuricemic rats[J]. Frontiers in Nutrition,2022,9:993951. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.993951

[58] WANG H N, LU M, DENG Y, et al. Lactobacillus brevis DM9218 ameliorates fructose-induced hyperuricemia through inosine degradation and manipulation of intestinal dysbiosis[J]. Nutrition,2019,62:63−73. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2018.11.018

[59] CAO J Y, WANG T, LIU Y S, et al. Lactobacillus fermentum F40-4 ameliorates hyperuricemia by modulating the gut microbiota and alleviating inflammation in mice[J]. Food & Function,2023,14(7):3259−3268.

[60] CHIEN C Y, CHIEN Y J, LIN Y H, et al. Supplementation of Lactobacillus plantarum (TCI227) prevented potassium-oxonate-induced hyperuricemia in rats[J]. Nutrients,2022,14(22):4832. doi: 10.3390/nu14224832

[61] LEE Y, WERLINGER P, SUH J W, et al. Potential probiotic Lacticaseibacillus paracasei MJM60396 prevents hyperuricemia in a multiple way by absorbing purine, suppressing xanthine oxidase and regulating urate excretion in mice[J]. Microorganisms,2022,10(5):851. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10050851

[62] WANG Z H, SONG L P, LI X P, et al. Lactiplantibacillus pentosus P2020 protects the hyperuricemia and renal inflammation in mice[J]. Frontiers in Nutrition,2023,10:1094483. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1094483

[63] YAMASAKI M, KIUE Y, FUJII K, et al. Vaccinium virgatum aiton leaves extract suppressed lipid accumulation and uric acid production in 3T3-L1 adipocytes[J]. Plants,2021,10(12):2638. doi: 10.3390/plants10122638

[64] LU Y J, SUN Q K, GUAN Q F, et al. The XOR-IDH3α axis controls macrophage polarization in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Journal of Hepatology,2023,79(5):1172−1184. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.06.022

[65] CHEN C Y, LÜ J M, YAO Q Z. Hyperuricemia-related diseases and xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) inhibitors:An overview[J]. Medical Science Monitor:International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research,2016,22:2501−2512.

[66] 牛春华, 肖茹雪, 赵子健, 等. 植物乳杆菌 UA149 的降尿酸作用[J]. 现代食品科技,2020,36(2):1−6. [NIU C H, XIAO R X, ZHAO Z J, et al. Serum uric acid lowering effect of Lactobacillus plantarum UA149 on hyperuricemic rats[J]. Modern Food Science and Technology,2020,36(2):1−6.] NIU C H, XIAO R X, ZHAO Z J, et al. Serum uric acid lowering effect of Lactobacillus plantarum UA149 on hyperuricemic rats[J]. Modern Food Science and Technology, 2020, 36(2): 1−6.

[67] CAO J Y, BU Y S, HAO H N, et al. Effect and potential mechanism of Lactobacillus plantarum Q7 on hyperuricemia in vitro and in vivo[J]. Frontiers in Nutrition,2022,9:954545. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.954545

[68] CAO J Y, LIU Q Q, HAO H N, et al. Lactobacillus paracasei X11 ameliorates hyperuricemia and modulates gut microbiota in mice[J]. Frontiers in Immunology,2022,13:940228. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.940228

[69] LEE Y, KIM N, WERLINGER P, et al. Probiotic characterization of Lactobacillus brevis MJM60390 and in vivo assessment of its antihyperuricemic activity[J]. Journal of Medicinal Food,2022,25(4):367−380. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2021.K.0171

[70] TIN A, MARTEN J, HALPERIN K V L, et al. Target genes, variants, tissues and transcriptional pathways influencing human serum urate levels[J]. Nature Genetics,2019,51(10):1459−1474. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0504-x

[71] NAKAYAMA A, NAKAOKA H, YAMAMOTO K, et al. GWAS of clinically defined gout and subtypes identifies multiple susceptibility loci that include urate transporter genes[J]. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases,2017,76(5):869−877. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209632

[72] NARANG R K, VINCENT Z, PHIPPS-GREEN A, et al. Population-specific factors associated with fractional excretion of uric acid[J]. Arthritis Research & Therapy,2019,21(1):1−9.

[73] TAKADA T, ICHIDA K, MATSUO H, et al. ABCG2 dysfunction increases serum uric acid by decreased intestinal urate excretion[J]. Nucleosides, Nucleotides and Nucleic Acids,2014,33(4−6):275−281. doi: 10.1080/15257770.2013.854902

[74] LI L J, ZHANG Y P, ZENG C C. Update on the epidemiology, genetics, and therapeutic options of hyperuricemia[J]. American Journal of Translational Research,2020,12(7):3167−3181.

[75] GE H Z, JIANG Z T, LI B, et al. Dendrobium officinalis six nostrum promotes intestinal urate underexcretion via regulations of urate transporter proteins in hyperuricemic rats[J]. Combinatorial Chemistry & High Throughput Screening,2023,26(4):848−861.

[76] OHASHI Y, TOYODA M, SAITO N, et al. Evaluation of ABCG2-mediated extra-renal urate excretion in hemodialysis patients[J]. Scientific Reports,2023,13(1):93. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-26519-x

[77] ICHIDA K. Recent progress and prospects for research on urate efflux transporter ABCG2[J]. Nihon rinsho Japanese Journal of Clinical Medicine,2014,72(4):757−765.

[78] YIN H, LIU N, CHEN J. The role of the intestine in the development of hyperuricemia[J]. Frontiers in Immunology,2022,13:845684. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.845684

[79] ZHAO H Y, CHEN X Y, MENG F Q, et al. Ameliorative effect of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus Fmb14 from Chinese yogurt on hyperuricemia[J]. Food Science and Human Wellness,2023,12(4):1379−1390. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2022.10.031

[80] LU L H, LIU T T, LIU X L, et al. Screening and identification of purine degrading Lactobacillus fermentum 9-4 from Chinese fermented rice-flour noodles[J]. Food Science and Human Wellness,2022,11(5):1402−1408. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2022.04.030

[81] 金方, 杨虹. 降血尿酸益生菌株的筛选和降血尿酸机理的探索[J]. 微生物学通报,2018,45(8):1757−1769. [JIN F, YANG H. Isolation of hypouricemic probiotics and exploration their effects on hyperuricemic rats[J]. Microbiology China,2018,45(8):1757−1769.] JIN F, YANG H. Isolation of hypouricemic probiotics and exploration their effects on hyperuricemic rats[J]. Microbiology China, 2018, 45(8): 1757−1769.

[82] YAMADA N, SAITO-IWAMOTO C, NAKAMURA M, et al. Lactobacillus gasseri PA-3 uses the purines IMP, inosine and hypoxanthine and reduces their absorption in rats[J]. Microorganisms,2017,5(1):10. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms5010010

[83] KUO Y W, HSIEH S H, CHEN J F, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri TSR332 and Lactobacillus fermentum TSF331 stabilize serum uric acid levels and prevent hyperuricemia in rats[J]. Peer J,2021,9:e11209. doi: 10.7717/peerj.11209

[84] ZHU J, LI Y J, CHEN Z G, et al. Screening of lactic acid bacteria strains with urate‐lowering effect from fermented dairy products[J]. Journal of Food Science,2022,87(11):5118−5127. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.16351

[85] MENG Y P, HU Y S, WEI M, et al. Amelioration of hyperuricemia by Lactobacillus acidophilus F02 with uric acid-lowering ability via modulation of NLRP3 inflammasome and gut microbiota homeostasis[J]. Journal of Functional Foods,2023,111:105903. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2023.105903

[86] LI M F, WU X L, GUO Z W, et al. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum enables blood urate control in mice through degradation of nucleosides in gastrointestinal tract[J]. Microbiome,2023,11(1):153. doi: 10.1186/s40168-023-01605-y

[87] 张沙沙, 窦清泉, 邹积宏. 降尿酸乳酸菌的筛选及其对高尿酸血症小鼠的影响[J]. 生物技术,2022,32(1):48−54,28. [ZHANG S S, DOU Q Q, ZOU J H. Screening of uric acid-lowering lactic acid bacteria and its effect on mice with hyperuricemia[J]. Biotechnology,2022,32(1):48−54,28.] ZHANG S S, DOU Q Q, ZOU J H. Screening of uric acid-lowering lactic acid bacteria and its effect on mice with hyperuricemia[J]. Biotechnology, 2022, 32(1): 48−54,28.

[88] LIANG L Z, MENG Z H, ZHANG F, et al. Lactobacillus gasseri LG08 and Leuconostoc mesenteroides LM58 exert preventive effect on the development of hyperuricemia by repairing antioxidant system and intestinal flora balance[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology,2023,14:1211831. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1211831

[89] SUN Y M, XU D M, ZHANG G M, et al. Wild-type Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 improves hyperuricemia by anaerobically degrading uric acid and maintaining gut microbiota profile of mice[J]. Journal of Functional Foods,2024,112:105935. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2023.105935

[90] SHI R J, YE J, FAN H, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum LLY-606 supplementation ameliorates hyperuricemia via modulating intestinal homeostasis and relieving inflammation[J]. Food & Function,2023,14(12):5663−5677.

[91] XU J, TU M L, FAN X K, et al. A novel strain of Levilactobacillus brevis PDD-5 isolated from salty vegetables has beneficial effects on hyperuricemia through anti-inflammation and improvement of kidney damage[J]. Food Science and Human Wellness,2024,13(2):898−908. doi: 10.26599/FSHW.2022.9250077

[92] LIU X, HAN C H, MAO T, et al. Commensal Enterococcus faecalis W5 ameliorates hyperuricemia and maintains the epithelium barrier in a hyperuricemia mouse model[J]. Journal of Digestive Diseases,2023,25(1):44−60.

[93] ZHANG L H, LIU J X, JIN T, et al. Live and pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila attenuate hyperuricemia in mice through modulating uric acid metabolism, inflammation, and gut microbiota[J]. Food & Function,2022,13(23):12412−12425.

[94] ZOU Y, RO K S, JIANG C T, et al. The anti-hyperuricemic and gut microbiota regulatory effects of a novel purine assimilatory strain, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum X7022[J]. European Journal of Nutrition, 2023, 63(3): 697-711.

[95] RO K S, ZHAO L, HU Y T, et al. Anti-hyperuricemic properties and mechanism of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum X7023[J]. Process Biochemistry,2024,136:26−37. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2023.11.008

[96] YIN S, ZHU F Y. Probiotics for constipation in Parkinson's:A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials[J]. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology,2022,12:1038928. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.1038928

[97] DE ALBERTI D, RUSSO R, TERRUZZI F, et al. Lactobacilli vaginal colonisation after oral consumption of Respecta® complex:A randomised controlled pilot study[J]. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics,2015,292(2):861−867.

[98] GOLDENBERG J Z, YAP C, LYTVYN L, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children[J]. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews,2017,12(12):CD006095.

[99] GUO Q, GOLDENBERG J Z, HUMPHREY C, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of pediatric antibiotic-associated diarrhea[J]. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews,2019,4(4):CD004827.

[100] SANDERS M E, AKKERMANS L M, HALLER D, et al. Safety assessment of probiotics for human use[J]. Gut microbes,2010,1(3):164−185. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.3.12127

[101] NOBRE L, FERNANDES C, FLORÊNCIO K, et al. Could paraprobiotics be a safer alternative to probiotics for managing cancer chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal toxicities?[J]. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research,2023,55(1):e12522.

[102] DEVI S M, ARCHER A C, HALAMI P M. Screening, characterization and in vitro evaluation of probiotic properties among lactic acid bacteria through comparative analysis[J]. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins,2015,7(3):181−192. doi: 10.1007/s12602-015-9195-5

[103] KHALESI S, BELLISSIMO N, VANDELANOTTE C, et al. A review of probiotic supplementation in healthy adults:helpful or hype?[J]. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition,2019,73(1):24−37. doi: 10.1038/s41430-018-0135-9

[104] ZHANG B, WANG Y P, TAN Z F, et al. Screening of probiotic activities of Lactobacilli strains isolated from traditional Tibetan Qula, a raw yak milk cheese[J]. Asian-Australas Journal of Animal Sciences,2016,29(10):1490−1499. doi: 10.5713/ajas.15.0849

[105] 江一帆, 滕建文, 黄丽, 等. 具有降解胆固醇益生活性和后生元特性的乳酸菌菌株筛选[J]. 食品科技,2023,48(9):9−16. [JIANG Y F, TENG J W, HUANG L, et al. Screening of lactic acid bacteria strains with cholesterol-degrading probiotic and postbiotic properties[J]. Food Science and Technology,2023,48(9):9−16.] JIANG Y F, TENG J W, HUANG L, et al. Screening of lactic acid bacteria strains with cholesterol-degrading probiotic and postbiotic properties[J]. Food Science and Technology, 2023, 48(9): 9−16.

[106] ISMAEL M, GU Y, CUI Y, et al. Lactic acid bacteria isolated from Chinese traditional fermented milk as novel probiotic strains and their potential therapeutic applications[J]. 3 Biotech,2022,12(12):337. doi: 10.1007/s13205-022-03403-z

[107] LI M, YANG D B, LU M, et al. Screening and characterization of purine nucleoside degrading lactic acid bacteria isolated from Chinese sauerkraut and evaluation of the serum uric acid lowering effect in hyperuricemic rats[J]. PLoS One,2014,9(9):e105577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105577

[108] GABA K, ANAND S. Incorporation of probiotics and other functional ingredients in dairy fat-rich products:Benefits, challenges, and opportunities[J]. Dairy,2023,4(4):630−649. doi: 10.3390/dairy4040044

-

期刊类型引用(2)

1. 韩丹,赵娅,黄恩善,叶树花,汪万进,吴方敏,王定良,章荣华. 生物活性肽联合益生菌干预对高尿酸血症患者血尿酸水平的影响. 预防医学. 2025(01): 40-45 .  百度学术

百度学术

2. 王琴,孙颖,任远庆,张荣,李育瑄. 降尿酸功能性益生菌的研究进展及在食品中的应用. 中外食品工业. 2024(17): 99-101 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(1)

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载: